Miscellaneous date-time functions

function isfinite() returns boolean

Here is the interesting part of the output from \df isfinite():

Result data type | Argument data types

------------------+-----------------------------

boolean | abstime

boolean | date

boolean | interval

boolean | timestamp with time zone

boolean | timestamp without time zone

The data type abstime is for internal use only. It inevitably shows up in the \df output. But you should simply forget that it exists.

Here's a trivial demonstration of the meaning of the function isfinite():

do $body$

begin

assert not isfinite( 'infinity'::timestamptz), 'Assert #1 failed';

assert not isfinite('-infinity'::timestamptz), 'Assert #2 failed';

end;

$body$;

The block finishes without error.

function age() returns interval

Nominally, age() returns the age of something "now" with respect to a date of birth. The value of "now" can be given: either explicitly, using the two-parameter overload, as the invocation's first actual argument; or implicitly, using the one-parameter overload, as date_trunc('day', clock_timestamp()). The value for the date of birth is given, for both overloads, as the invocation's last actual argument. Of course, this statement of purpose is circular because it avoids saying precisely how age is defined—and why a notion is needed that's different from what is given simply by subtracting the date of birth from "now", using the native minus operator, -.

Here is the interesting part of the output from \df age(). The rows were re-ordered manually and whitespace was manually added to improve the readability:

Result data type | Argument data types

------------------+----------------------------------------------------------

interval | timestamp without time zone, timestamp without time zone

interval | timestamp with time zone, timestamp with time zone

interval | timestamp without time zone

interval | timestamp with time zone

The 'xid' overload of 'age()' has nothing to do with date-time data types

There's an overload with xid argument data type (and with integer return). The present Date and time data types major section does not describe the xid overload of age().This section first discusses age as a notion. Then it defines the semantics of the two-parameter overload of the built-in age() function by modeling its implementation. The semantics of the one-parameter overload is defined trivially in terms of the semantics of the two-parameter overload.

The definition of age is a matter of convention

Age is defined as the length of time that a person (or a pet, a tree, a car, a building, a civilization, the planet Earth, the Universe, or any phenomenon of interest) has lived (or has been in existence). Here is a plausible formula in the strict domain of date-time arithmetic:

age ◄— todays_date - date_of_birth

If todays_date and date_of_birth are date values, then age is produced as an int value. And if todays_date and date_of_birth are plain timestamp values (or timestamptz values), then age is produced as an interval value. As long as the time-of-day component of each plain timestamp value is exactly 00:00:00 (and this is how people think of dates and ages) then only the dd component of the internal [mm, dd, ss] representation of the resulting interval value will be non-zero. Try this:

drop function age_in_days(text, text);

create function age_in_days(today_text in text, dob_text in text)

returns table (z text)

language plpgsql

as $body$

declare

d_today constant date not null := today_text;

d_dob constant date not null := dob_text;

t_today constant timestamp not null := today_text;

t_dob constant timestamp not null := dob_text;

begin

z := (d_today - d_dob)::text; return next;

z := (t_today - t_dob)::text; return next;

end;

$body$;

select z from age_in_days('290000-08-17', '0999-01-04 BC');

This is the result:

106285063

106285063 days

The value of the 'dd' field has an upper limit of 109,203,124

See the subsection procedure assert_interval_days_in_range (days in bigint) on the Custom domain types for specializing the native interval functionality page.However, how ages are stated is very much a matter of convention. Beyond, say, one's mid teens, it is given simply as an integral number of years. (Sue Townsend's novel title, "The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13 3/4", tells the reader that it's a humorous work and that Adrian is childish for his years.) The answer to "What is the age of the earth?" is usually given as "about 4.5 billion years"—and this formulation implies that a precision of about one hundred thousand years is appropriate. At the other end of the spectrum, the age of new born babies is usually given first as an integral number of days, and later, but while still a toddler, as an integral number of months. Internet search finds articles with titles like "Your toddler's developmental milestones at 18 months". You'll even hear age given as, say, "25 months".

Internet search finds lots of formulas to calculate age in years—usually using spreadsheet arithmetic. It's easy to translate what they do into SQL primitives. The essential point of the formula is that if today's month-and-date is earlier in the year than the month-and-date of the date-of-birth, then you haven't yet reached your birthday.

Try this:

drop function age_in_years(text, text);

create function age_in_years(today_tz in timestamptz, dob_tz in timestamptz)

returns interval

language plpgsql

as $body$

declare

d_today constant date not null := today_tz;

d_dob constant date not null := dob_tz;

yy_today constant int not null := extract(year from d_today);

mm_today constant int not null := extract(month from d_today);

dd_today constant int not null := extract(day from d_today);

yy_dob constant int not null := extract(year from d_dob);

mm_dob constant int not null := extract(month from d_dob);

dd_dob constant int not null := extract(day from d_dob);

mm_dd_today constant date not null := make_date(year=>1, month=>mm_today, day=>dd_today);

mm_dd_dob constant date not null := make_date(year=>1, month=>mm_dob, day=>dd_dob);

-- Is today's mm-dd greater than dob's mm-dd?

delta constant int not null := case

when mm_dd_today >= mm_dd_dob then 0

else -1

end;

age constant interval not null := make_interval(years=>(yy_today - yy_dob + delta));

begin

return age;

end;

$body$;

set timezone = 'America/Los_Angeles';

select

age_in_years('2007-02-13', '1984-02-14')::text as "age one day before birthday",

age_in_years('2007-02-14', '1984-02-14')::text as "age on birthday",

age_in_years('2007-02-15', '1984-02-14')::text as "age one day after birthday",

age_in_years(clock_timestamp(), '1984-02-14')::text as "age right now";

This is the result (when the select is executed in October 2021):

age one day before birthday | age on birthday | age one day after birthday | age right now

-----------------------------+-----------------+----------------------------+---------------

22 years | 23 years | 23 years | 37 years

You can easily derive the function age_in_months() from the function age_in_years(). Then, with all three functions in place, age_in_days(), age_in_months(), and age_in_years(), you can implement an age() function that applies a rule-of-thumb, based on threshold values for what age_in_days() returns, to return either a pure days, a pure months, or a pure years interval value. This is left as an exercise for the reader.

The semantics of the built-in function age()

The following account relies on understanding the internal representation of an 'interval' value

The internal representation of an interval value is a [mm, dd, ss] tuple. This is explained in the section How does YSQL represent an interval value?.Bare timestamp subtraction produces a result where the yy field is always zero and only the mm and dd fields might be non-zero, thus:

select (

'2001-04-10 12:43:17'::timestamp -

'1957-06-13 11:41:13'::timestamp)::text;

This is the result:

16007 days 01:02:04

See the section The moment-moment overloads of the "-" operator for timestamptz, timestamp, and time for more information.

The PostgreSQL documentation, in Table 9.30. Date/Time Functions, describes how age() calculates its result thus:

Subtract arguments, producing a "symbolic" result that uses years and months, rather than just days

and it gives this example:

select age(

'2001-04-10'::timestamp,

'1957-06-13'::timestamp)::text;

with this result:

43 years 9 mons 27 days

Because the result data type is interval, and there's no such thing as a "symbolic" interval value, this description is simply nonsense. It presumably means that the result is a hybrid interval value where the yy field might be non-zero.

'age(t2, ts1)' versus 'justify_interval(ts2 - ts1)'

While, as was shown above, subtracting one timestamp[tz] value from another produces an interval value whose mm component is always zero, you can use justify_interval() to produce a value that, in general, has a non-zero value for each of the mm, dd_, and ss components. However, the actual value produced by doing this will, in general, differ from that produced by invoking age(), even when the results are compared with the native equals operator, =, (and not the user-defined "strict equals" operator, ==). Try this:

set timezone = 'UTC';

with

c1 as (

select

'2021-03-17 13:43:19 America/Los_Angeles'::timestamptz as ts2,

'2000-05-19 11:19:13 America/Los_Angeles'::timestamptz as ts1),

c2 as (

select

age (ts2, ts1) as a,

justify_interval(ts2 - ts1) as j

from c1)

select

a::text as "age(ts2, ts1)",

j::text as "justify_interval(ts2 - ts1)",

(a = j)::text as "age() = justify_interval() using native equals"

from c2;

This is the result:

age(ts2, ts1) | justify_interval(ts2 - ts1) | age() = justify_interval() using native equals

----------------------------------+---------------------------------+------------------------------------------------

20 years 9 mons 29 days 02:24:06 | 21 years 1 mon 17 days 02:24:06 | false

They differ simply because justify_interval() uses one rule (see the subsection The justify_hours(), justify_days(), and justify_interval() built-in functions) and age() uses a different rule (see the subsection The semantics of the two-parameter overload of function age()). You should understand the rule that each uses and then decide what you need. But notice Yugabyte's recommendation, below, simply to avoid using the built-in age() function.

Anyway, the phrase producing a "symbolic" result gives no clue about how age() works in the general case. But it looks like this is what it did with the example above:

-

It tried to subtract "13 days" from "10 days" and "borrowed" one month to produce a positive result. As it happens, both June and April have 30 days (with no leap year variation). The result, "(30 + 10) - 13", is "27 days".

-

It tried to subtract "6 months" from "3 months" (decremented by one month from its starting value, "4 months", to account for the "borrowed" month), and "borrowed" one year to produce a positive result. One year is always twelve months. The result, "(12 + 3) - 6", is "9 months".

-

Finally, it subtracted "1957 years" from "2000 years" (decremented by one year from its starting value, "2021 years", to account for the "borrowed" year).

Here is another example of the result that age() produces when the inputs have non-zero time-of-day components:

select age(

'2001-04-10 11:19:17'::timestamp,

'1957-06-13 15:31:42'::timestamp)::text;

with this result:

43 years 9 mons 26 days 19:47:35

Nobody ever cites an age like this, with an hours, minutes, and seconds component. But the PostgreSQL designers thought that it was a good idea to implement age() to do this.

Briefly, and approximately, the function age() extracts the year, month, day, and seconds since midnight for each of the two input moment values. It then subtracts these values pairwise and uses them to create an interval value. In general, this will be a hybrid value with non-zero mm, dd, and ss components. But the statement of the semantics must be made more carefully than this to accommodate the fact that the outcomes of the pairwise differences might be negative.

- For example, if today is "year 2020 month 4" and if the date-of-birth is "year 2010 month 6", then a naïve application of this rule would produce an age of "10 years -2 months". But age is never stated like this. Rather, it's stated as "9 years 10 months". This is rather like doing subtraction of distances measured in imperial feet and inches. When you subtract "10 feet 6 inches" from "20 feet 4 inches" you "borrow" one foot, taking "10 feet" down to "9 feet" so that you can subtract "6 inches" from "12 + 4 inches" to get "10 inches".

However, the borrowing rules get very tricky with dates because "borrowed" months (when pairwise subtraction of day values would produce a negative result) have different numbers of days (and there's leap years to account for too) so the "borrowing" rules get to be quite baroque—so much so that it's impractical to explain the semantics of age() in prose. Rather, you need to model the implementation. PL/pgSQL is perfect for this.

The full account of age() is presented on its own dedicated child page.

Avoid using the built-in 'age()' function.

The rule that age() uses to produce its result cannot be expressed clearly in prose. And, anyway, it produces a result with an entirely inappropriate apparent precision. Yugabyte recommends that you decide how you want to define age for your present use case and then implement the definition that you choose along the lines used in the user-defined functions age_in_days() and age_in_years() shown above in the subsection The definition of age is a matter of convention.function extract() | function date_part() returns double precision

The function extract(), and the alternative syntax that the function date_part() supports for the same semantics, return a double precision value corresponding to a nominated so-called field, like year or second, from the input date-time value.

The full account of extract() and date_part() is presented on its own dedicated child page.

function timezone() | 'at time zone' operator returns timestamp | timestamptz

The function timezone(), and the alternative syntax that operator at time zone supports for the same semantics, return a plain timestamp value from a timestamptz input or a timestamptz value from a plain timestamp input. The effect is the same as if a simple typecast is used from one data type to the other after using set timezone to specify the required timezone.

timezone(<timezone>, timestamp[tz]_value) == timestamp[tz]_value at time zone <timezone>

Try this example:

with c as (

select '2021-09-22 13:17:53.123456 Europe/Helsinki'::timestamptz as tstz)

select

(timezone('UTC', tstz) = tstz at time zone 'UTC' )::text as "with timezone given as text",

(timezone(make_interval(), tstz) = tstz at time zone make_interval())::text as "with timezone given as interval"

from c;

This is the result:

with timezone given as text | with timezone given as interval

-----------------------------+---------------------------------

true | true

(Because all make_interval()'s formal parameters have default values of zero, you can invoke it with no actual arguments.)

Now try this example:

set timezone = 'UTC';

with c as (

select '2021-09-22 13:17:53.123456 Europe/Helsinki'::timestamptz as tstz)

select

(timezone('UTC', tstz) = tstz::timestamp)::text

from c;

The result is true.

The function syntax is more expressive than the operator syntax because its overloads distinguish explicitly between specifying the timezone by name or as an interval value. Here is the interesting part of the output from \df timezone(). The rows were re-ordered manually and whitespace was manually added to improve the readability:

Result data type | Argument data types

-----------------------------+---------------------------------------

timestamp with time zone | text, timestamp without time zone

timestamp without time zone | text, timestamp with time zone

timestamp with time zone | interval, timestamp without time zone

timestamp without time zone | interval, timestamp with time zone

The rows for the timetz argument data types were removed manually, respecting the recommendation here to avoid using this data type. (You can't get \df output for the operator at time zone.)

Avoid using the 'at time zone' operator and use only the function 'timezone()'.

Because the function syntax is more expressive than the operator syntax, Yugabyte recommends using only the former syntax. Moreover, never use timezone() bare but, rather, use it only via the overloads of the user-defined wrapper function at_timezone() and as described in the section Recommended practice for specifying the UTC offset.'overlaps' operator returns boolean

The account of the overlaps operator first explains the semantics in prose and pictures. Then it presents two implementations that model the semantics and shows that they produce the same results.

'overlaps' semantics in prose

The overlaps operator determines if two durations have any moments in common. The overlaps invocation defines a duration either by its bounding moments or by its one bounding moment and the size of the duration (expressed as an interval value). There are therefore four alternative general invocation syntaxes. Either:

overlaps_result ◄— (left-duration-bound-1, left-duration-bound-2) overlaps (right-duration-bound-1, right-duration-bound-2)

or:

overlaps_result ◄— (left-duration-bound-1, left-duration-size) overlaps (right-duration-bound-1, right-duration-bound-2)

or:

overlaps_result ◄— (left-duration-bound-1, left-duration-bound-2) overlaps (right-duration-bound-1, right-duration-size)

or:

overlaps_result ◄— (left-duration-bound-1, left-duration-size) overlaps (right-duration-bound-1, right-duration-size)

Unlike other phenomena that have a length, date-time durations are special because time flows inexorably from earlier moments to later moments. It's convenient to say that, when the invocation as presented has been processed, a duration is ultimately defined by its start moment and its finish moment—even if one of these is derived from the other by the size of the duration. In the degenerate case, where the start and finish moments coincide, the duration becomes an instant.

Notice that, while it's natural to write the start moment before the finish moment, the result is insensitive to the order of the boundary moments or to the sign of the size of the duration. The result is also insensitive to which duration, "left" or "right" is written first.

This prose account of the semantics starts with some simple examples. Then it states the rules carefully and examines critical edges cases.

Simple examples.

Here's a simple positive example:

select (

('07:00:00'::time, '09:00:00'::time) overlaps

('08:00:00'::time, '10:00:00'::time)

)::text as "time durations overlap";

This is the result:

time durations overlap

------------------------

true

And here are some invocation variants that express durations with the same ultimate derived start and finish moments:

do $body$

declare

seven constant time not null := '07:00:00';

eight constant time not null := '08:00:00';

nine constant time not null := '09:00:00';

ten constant time not null := '10:00:00';

two_hours constant interval not null := make_interval(hours=>2);

r1 constant boolean not null := (seven, nine) overlaps (eight, ten);

r2 constant boolean not null := (seven, two_hours) overlaps (eight, ten);

r3 constant boolean not null := (seven, nine) overlaps (eight, two_hours);

r4 constant boolean not null := (seven, two_hours) overlaps (eight, two_hours);

r5 constant boolean not null := (nine, seven) overlaps (ten, eight);

r6 constant boolean not null := (nine, -two_hours) overlaps (ten, -two_hours);

begin

assert ((r1 = r2) and (r1 = r3) and (r1 = r4) and (r1 = r5) and (r1 = r6)), 'Assert failed';

end;

$body$;

The block finishes silently, showing that the result from each of the six variants is the same.

The operator is supported by the overlaps() function. Here is the interesting part of the output from \df overlaps():

Result data type | Argument data types

------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

boolean | time, time, time, time

boolean | time, interval, time, time

boolean | time, time, time, interval

boolean | time, interval, time, interval

boolean | timestamp, timestamp, timestamp, timestamp

boolean | timestamp, interval, timestamp, timestamp

boolean | timestamp, timestamp, timestamp, interval

boolean | timestamp, interval, timestamp, interval

boolean | timestamptz, timestamptz, timestamptz, timestamptz

boolean | timestamptz, interval, timestamptz, timestamptz

boolean | timestamptz, timestamptz, timestamptz, interval

boolean | timestamptz, interval, timestamptz, interval

The rows for the timetz argument data types were removed manually, respecting the recommendation here to avoid using this data type. Also, to improve the readability:

- the rows were reordered

- time without time zone was rewritten as time,

- timestamp without time zone was rewritten as timestamp,

- timestamp with time zone was rewritten as timestamptz,

- blank rows and spaces were inserted manually

This boils down to saying that overlaps supports durations whose boundary moments are one of time, plain timestamp, or timestamptz. There is no support for date durations. But you can achieve the functionality that such support would bring simply by typecasting date values to plain timestamp values and using the plain timestamp overload. If you do this, avoid the overloads with an interval argument because of the risk that a badly-chosen interval value will result in a boundary moment with a non-zero time component. Rather, achieve that effect by adding an integer value to a date value before typecasting to plain timestamp.

Here is an example:

select (

( ('2020-01-01'::date)::timestamp, ('2020-01-01'::date + 2)::timestamp ) overlaps

( ('2020-01-02'::date)::timestamp, ('2020-01-01'::date + 2)::timestamp )

)::text as "date durations overlap";

This is the result:

date durations overlap

------------------------

true

Rule statement and edge cases

Because (unless the duration collapses to an instant) one of the boundary moments will inevitably be earlier than the other, it's useful to assume that some pre-processing has been done and to write the general invocation syntax using the vocabulary start-moment and finish-moment. Moreover (except when both durations start at the identical moment and finish at the identical moment), it's always possible to decide which is the earlier-duration and which is the later-duration. Otherwise (when the two durations exactly coincide), it doesn't matter which is labeled earlier and which is labeled later.

-

If the left-duration's start-moment is less than the right-duration's start-moment, then the left-duration is the earlier-duration and the right-duration is the later-duration.

-

If the right-duration's start-moment is less than the left-duration's start-moment, then the right-duration is the earlier-duration and the left-duration is the later-duration.

-

Else, if the left-duration's start-moment and the right-duration's start-moment are identical, then

-

If the left-duration's finish-moment is less than the right-duration's finish-moment, then the left-duration is the earlier-duration and the right-duration is the later-duration.

-

If the right-duration's finish-moment is less than the left-duration's finish-moment, then the right-duration is the earlier-duration and the left-duration is the later-duration.

-

It's most useful, in order to express the rules and to discuss the edge cases, to write the general invocation syntax using the vocabulary earlier-duration and later-duration together with start-moment and finish-moment, thus:

overlaps_result ◄— (earlier-duration-start-moment, earlier-duration-finish-moment) overlaps (later-duration-start-moment, later-duration-finish-moment)

The overlaps operator treats a duration as a closed-open range. In other words:

duration == [start-moment, finish-moment)

However, even when a duration collapses to an instant, it is considered to be non-empty. (When the end-points of a '[)' range value are identical, this value is considered to be empty and cannot overlap with any other range value.)

Because the start-moment is included in the duration but the finish-moment is not, this leads to the requirement to state the following edge case rules. (These rules were established by the SQL Standard.)

- If the left duration is not collapsed to an instant, and the left-duration-finish-moment is identical to the right-duration-start-moment, then the two durations do not overlap. This holds both when the right duration is not collapsed to an instant and when it is so collapsed.

- If the left duration is collapsed to an instant, and the left-duration-start-and-finish-moment is identical to the right-duration-start-moment, then the two durations do overlap. This holds both when the right duration is not collapsed to an instant and when it is so collapsed. In other words, when two instants coincide, they do overlap.

Notice that these rules are different from those for the && operator between a pair of '[)' range values. (The && operator is also referred to as the overlaps operator for range values.) The differences are seen, in some cases, when instants are involved. Try this:

with

c1 as (

select '2000-01-01 12:00:00'::timestamp as the_instant),

c2 as (

select

the_instant,

tsrange(the_instant, the_instant, '[)') as instant_range -- notice '[)'

from c1)

select

the_instant,

isempty(instant_range) ::text as "is empty",

( (the_instant, the_instant) overlaps (the_instant, the_instant) )::text as "overlaps",

( instant_range && instant_range )::text as "&&"

from c2;

This is the result:

the_instant | is empty | overlaps | &&

---------------------+----------+----------+-------

2000-01-01 12:00:00 | true | true | false

In order to get the outcome true from the && operator, you have to change definition of the ranges from open-closed, '[)', to open-open, '[]', thus:

with

c1 as (

select '2000-01-01 12:00:00'::timestamp as the_instant),

c2 as (

select

the_instant,

tsrange(the_instant, the_instant, '[]') as instant_range -- notice '[]'

from c1)

select

the_instant,

isempty(instant_range) ::text as "is empty",

( (the_instant, the_instant) overlaps (the_instant, the_instant) )::text as "overlaps",

( instant_range && instant_range )::text as "&&"

from c2;

This is the new result:

the_instant | is empty | overlaps | &&

---------------------+----------+----------+------

2000-01-01 12:00:00 | false | true | true

It doesn't help to ask why the rules are different for the overlaps operator acting between two explicitly specified durations and the && acting between two range values. It simply is what it is—and the rules won't change.

Notice that you can make the outcomes of the overlaps operator and the && operator agree for all tests. But to get this outcome, you must surround the use of && with some if-then-else logic to choose when to use '[)' and when to use '[]'. Code that does this is presented on this dedicated child page.

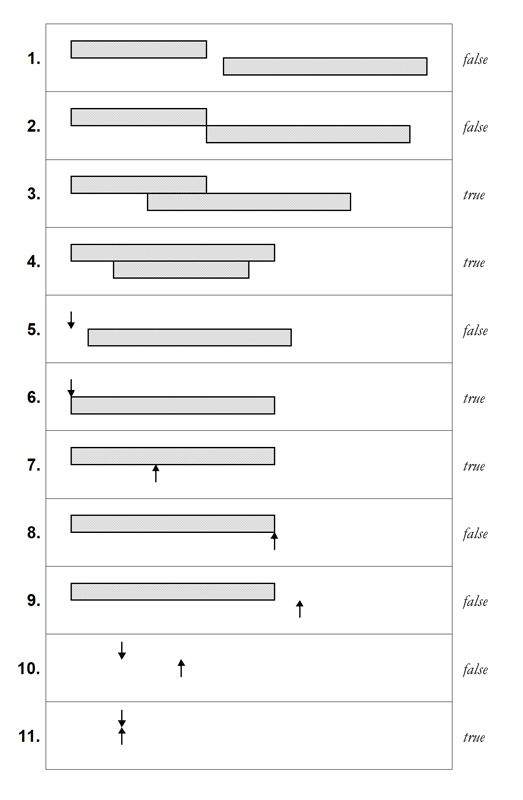

'overlaps' semantics in pictures

The following diagram shows all the interesting cases.

Two implementations that model the 'overlaps' semantics and that produce the same results

These are presented and explained on this dedicated child page. The page also presents the tests that show that, for each set of inputs that jointly probe all the interesting cases, the two model implementations produce the same result as each other and the same result as the native overlaps operator, thus:

TWO FINITE DURATIONS

--------------------

1. Durations do not overlap 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-05-15 00:00:00 | 2000-08-15 00:00:00, 2000-12-15 00:00:00 false

2. Right start = left end 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-05-15 00:00:00 | 2000-05-15 00:00:00, 2000-12-15 00:00:00 false

3. Durations overlap 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-08-15 00:00:00 | 2000-05-15 00:00:00, 2000-12-15 00:00:00 true

3. Durations overlap by 1 microsec 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-06-15 00:00:00.000001 | 2000-06-15 00:00:00, 2000-12-15 00:00:00 true

3. Durations overlap by 1 microsec 2000-06-15 00:00:00, 2000-12-15 00:00:00 | 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-06-15 00:00:00.000001 true

4. Contained 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-12-15 00:00:00 | 2000-05-15 00:00:00, 2000-08-15 00:00:00 true

4. Contained, co-inciding at left 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-06-15 00:00:00 | 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-08-15 00:00:00 true

4. Contained, co-inciding at right 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-06-15 00:00:00 | 2000-02-15 00:00:00, 2000-06-15 00:00:00 true

4. Durations coincide 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-06-15 00:00:00 | 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-06-15 00:00:00 true

ONE INSTANT, ONE FINITE DURATION

--------------------------------

5. Instant before duration 2000-02-15 00:00:00, 2000-02-15 00:00:00 | 2000-03-15 00:00:00, 2000-04-15 00:00:00 false

6. Instant coincides with duration start 2000-02-15 00:00:00, 2000-02-15 00:00:00 | 2000-02-15 00:00:00, 2000-03-15 00:00:00 true

7. Instant within duration 2000-02-15 00:00:00, 2000-02-15 00:00:00 | 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-03-15 00:00:00 true

8. Instant coincides with duration end 2000-02-15 00:00:00, 2000-02-15 00:00:00 | 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-02-15 00:00:00 false

9. Instant after duration 2000-05-15 00:00:00, 2000-05-15 00:00:00 | 2000-03-15 00:00:00, 2000-04-15 00:00:00 false

TWO INSTANTS

------------

10. Instants differ 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-01-15 00:00:00 | 2000-06-15 00:00:00, 2000-06-15 00:00:00 false

11. Instants coincide 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-01-15 00:00:00 | 2000-01-15 00:00:00, 2000-01-15 00:00:00 true